|

INTRODUCTION

THE chief by-product of the Great War is the revelation made

to this generation that we associate every day with men of heroic

mould. Before the call to battle came, we had not the vision to

see the stuff of which our American youngsters were made. When

the hour for achievement struck, we discovered all about us men

who by valor and initiative and resource not only preserved all

the best traditions, but made new and glorious traditions.

The story of the President Lincoln is one that thrills, for it

is a concrete case of how Navy men meet emergencies and look death

in the face with out a qualm. Lieutenant Isaacs has told the story

of its torpedoing and of the courage of its captain and all on

board in a way to increase the confidence and admiration we have

for men in the naval service. His recital of his capture, his

rare experiences, his alertness to secure information that would

aid his country, his resolve to find or make a way to escape and

bring back the knowledge his terrible experiences had imparted,

his resourcefulness and will to overcome what seemed insuperable

obstacles—these make a story that will live in the annals

of naval daring and naval disregard of danger.

JOSEPHUS DANIELS

(Back to

Contents)

|

|

Prisoner

of the U-90

PROLOGUE

THE old Hamburg-American liner President Lincoln

was one of the German ships taken over by the United States when

the President announced that a state of war was considered to

exist between America and Germany. She was considerably damaged

by the Huns before they were taken off and interned, but within

six months had been repaired and fitted up as a Navy transport

mounting four six-inch guns and capable of carrying 5000 troops

and 8000 tons of cargo. Her name, that of one of our most illustrious

Presidents, was left unchanged, and she shoved off from Hoboken

piers on October I8, I9I7, bound for St. Nazaire, France, on her

maiden voyage as an American man-o'- war.

(Back to

Contents)

|

|

CHAPTER I

THE SINKING

THE morning of May 3I, 1918 broke clear and cool. We had left

the coast of France behind and were running west with a fair breeze

in company with three other transports.

The U.S.S. President Lincoln, the Navy's most useful transport,

in returning light from her fifth trip to France since America

entered the Great War, was making twelve and a half knots, although

had she been alone standard speed would have been her maximum

of fifteen knots. The escorting destroyers had left us the preceding

evening twenty-four hours out from Brest. A few hours later, as

we were running with all lights out and zigzagging according to

plan, the German submarine U-90 cruising on the surface at six

knots speed sighted us by the light of the moon. Increasing her

speed she trailed us unknown to the convoy. We were four huge

shapes looming up in the darkness and visible to her over a mile

away—she was a small black object lying low in the water

and visible for not more than a quarter of a mile.

All night she trailed us until her captain was sure of our base

course. Then, circling around, he made a wide detour and took

up his position intercepting our course and a few miles ahead.

When we bore in sight he submerged and approached to the attack.

At eight o'clock, the gunnery officer forward and I aft, came

off watch from the control towers after a night of practically

no sleep. We were finishing breakfast. Two bells had just struck.

Suddenly the ship was rocked by a double explosion, the second

following the first with scarcely a perceptible interval between.

We instantly rushed to our battle stations, and that was the last

I saw of any of the heads of departments, for my station was aft

alone, theirs were forward.

As I ran aft another explosion shook the ship. The first two

had been forward, but this one was aft directly in my path. The

force of the explosion crushed in No. 12 lifeboat and threw it

up on deck not ten feet from where I stood, but only showered

me with water. The submarine had approached, submerged, to within

eight hundred yards of us with only the periscope showing. She

was directly ahead of the ship; on our left, but disregarded her

in the endeavor to "get" us the Big One, and on e of

the two six-masted steamers in the world," as he afterwards

said. He aimed for No. 2 mast and fired two torpedoes, and the

aiming for No. 4 mast he fired the third. All were perfect hits.

When I reached the after control tower all guns and boats were

manned and perfect discipline prevailed . This was the "green"

crew of over six hundred men who eight months before had never

seen a man-o"-war, not to speak of ever having manned one.

At ten minutes past nine I received the report that holds No.

5 and No. Six were flooded and the water approaching No. 1 deck.

I reported this over the telephone to the captain, who ordered

me to abandon ship. At nine-fifteen all hands aft were off the

ship in lifeboats and on rafts. The main deck was then within

a few inches of the surface of the sea, for we had been gradually

settling since the third explosion. In fact some waves were already

washing over the deck. I then jumped on a life-raft with my messenger,

who had never left me, and together we tied our raft to those

near by; then giving our painter to one of the boats, I ordered

them to pull away from the sinking ship. At nine-thirty we were

well clear, and the old ship, turning over gently to starboard,

put her nose in the air and went down. As the waters closed over

her we rose and gave three cheers for the President Lincoln ---

the best ship that ever carried troops in the cause of Freedom.

(Back to

Contents)

|

|

CHAPTER II

CAPTURED

FOR fifteen minutes after the Lincoln went down, we busied ourselves

tying together rafts and boats in order that they would not be

scattered over the ocean and so that the survivors could be easily

and quickly picked up by the rescuing vessels when they should

arrive on the scene.

Debris of all kinds was floating about— immense timbers,

broken topmasts, and other gear were being propelled out of the

water in all directions. There was great danger of some of these

striking us, but fortunately none found a mark. Finally, after

being in the water on the raft for three quarters of an hour,

a half-filled boat happened along and picked me up.

About this time, the other three ships having disappeared in the

distance, the submarine came to the surface and approached the

boat. In answer to the entreaties of the men in my boat I lay

back in the stern sheets and covered the gold stripes on my sleeves

with my body. I could not bring myself to the humiliation of hiding

in the bottom of the boat and leaving them to face alone the displeasure

of the pirates, although they begged me to do so or at least to

remove my uniform. I saw later, however, that there was no use

in trying to deceive the captain, for the submarine approached

to within fifty yards and he could at that short distance readily

distinguish every detail of uniform. I had lost my cap, but had

on an old blouse under my lifejacket. Recognizing this, the commanding

officer of the U-boat put a megaphone to his lips and sang out,

" Come aboard." We pulled alongside, and as I rose to

step out of the lifeboat, the men, realizing that I was about

to leave them, perhaps never to return, raised their voices in

protest and tried to restrain me. I turned to calm them, telling

them not to worry, that it was only the fortunes of war, and stepping

on the gunwale I grasped the hands of those nearest me in a heartfelt

good-bye and jumped on the deck of the submarine. I had endeavored

to wear as pleasant an expression on my face as I could muster

in that trying time, although, as I released the fingers of my

little gunner Cochrane, I felt I was bidding farewell to a real

friend for perhaps the last time.

As I walked along the deck a German sailor came behind me and

took my pistol. I then gave him the whole belt. Going up to the

conning tower I saluted the officer whom I took to be the captain.

He addressed me in rather fair English as follows:

"Are you the captain of the President Lincoln? "

"No, sir," I replied. "I believe the captain went

down with the ship, for I have not seen him since. I am the first

lieutenant.

"I am Captain Remy," he said. "My orders are to

take the senior officer prisonerwhenever I sink a man-o'-war.

You will remain aboard and point out your captain to me."

At that time Captain Foote, of the Lincoln, was pulling stroke

oar in one of the lifeboats. It was his duty to remain with his

men and so be in a position to look after their safety until aided

by rescuing vessels. The manner in which he performed this duty

is one of the most striking incidents of the Great War. Of the

seven hundred souls aboard the President Lincoln only twenty-three

men and three officers were lost, and that a greater loss of life

did not result must be attributed to the grand discipline which

prevailed, for which he alone was responsible, and to his coolness

and skill in the long trying hours which elapsed before destroyers

arrived at eleven o'clock that night.

When Captain Remy finished speaking he offered me a glass of sherry,

which I took with thanks, for the water had been rather cold and

I was numb from my waist down. We then cruised slowly among the

boats and rafts. I sang out to two or three boats and asked if

they had seen the captain. Receiving negative replies I turned

to Captain Remy and told him I was sure my captain had gone down

with the ship. Thereupon he sent me below and gave me warm clothing.

The submarine then left the scene of the sinking and cruised

up and down on the surface for the next two days. Early the following

morning a radio message from an American destroyer was intercepted

and Captain Remy gave it to me to read. It said: "President

Lincoln sunk. Survivors saved. A few missing."

(Back to

Contents)

|

IN cruising in that vicinity we were merely following out what

appeared to be Remy's routine schedule. He called those waters

his cruising ground. We remained constantly on the surface,

submerging only when it became necessary to avoid ships, and

once a day to get the proper trim. I was up on deck most of

the time standing on the conning platform behind the officer

of the deck. The weather was moderate, and although we rolled

slightly it was dry and comfortable there. I had plenty of time

to look at the sea and the sky and review my novel situation.

When I was ordered to the President Lincoln from the Fleet and

realized that I would actually have an opportunity to do my

share in the winning of the war, I was pleased beyond description.

I rather expected to be wounded or killed or even drowned, for

I conjectured that if the "game" went on long enough

it was only natural that, by the laws of choice and chance,

the Lincoln would finally be torpedoed; and with her torpedoed

and sunk it was to be expected that some would be wounded, some

killed outright, some drowned, and the remainder rescued little

the worse for the experience. But never once had the thought

of being taken prisoner entered my mind; I dare say it is or

was the same with the most of us. And so I had food for thought

during those first few days, and the more I thought about it

the less I liked it. The only one taken among the seven hundred

souls on the President Lincoln! Worse still, the only United

States Navy Officer captured by the Germans during the war!

I decided it could not be.

The afternoon of June Ist, about five o'clock, as we were sitting

in the tiny wardroom sipping our "Kaffee," the officer

who had the watch on deck sent word to the captain that two

ships had been sighted. They were two American destroyers, apparently

the ones who had picked up the survivors of the President Lincoln,

and were on their way back to Brest. Remy went on deck, took

the cone, and turning away from the destroyers went full speed

ahead. Just at this time the submarine was sighted by the destroyers

who gave chase. When Remy found he was seen, he quickly submerged

and zigzagged while making about eight knots speed. We ran at

a depth of two hundred feet. All officers and men were at their

stations—I was alone in the wardroom with no companions

but Hope and Fear: hope that they would "get" the

submarine and fear of that very eventuality.

We were submerged but a few minutes when a dull concussion slightly

rocked the boat. It was the first depth bomb! Others followed

in quick succession until a total of twenty-two were counted.

Inside the submarine it was as quiet as the grave —the

only sounds that broke the stillness were the frequent reports

from the petty officer at the microphones to the captain telling

him when the sounds of the destroyers' propellers showed they

were approaching or receding and in which direction.

Five of the depth bombs exploded so close that the boat was

shaken from stem to stern, and I fully expected to see the seams

open and the water rush in. At that time I did not know which

side I was cheering for. But she stood the shocks well, and

soon the sound of the propellers grew fainter and fainter, and

finally could be heard no more. We remained submerged an hour

longer and then came to the surface finding all serene and calm

again.

During the "show" I looked into the control room to

see how officers and men were taking their medicine. There was

one cool person among the five officers and forty-two men and

he was the captain. I saw two of the officers shaking their

heads over the affair, and the blanched faces of the crew told

better than words what their feelings were. Remy afterwards

told me there was one part of his business he dreaded more than

what I had just witnessed—and that was the passing through

unknown mine fields.

The following morning, June 2d, we sighted another American

destroyer. This time Remy took no chances of being seen, but

submerged immediately.

(Back to

Contents)

|

CHAPTER IV

THE U-90

The U-90 was built in 1916 and was commissioned in I9I7. She was

about two hundred feet long and mounted a four-inch gun forward

and another aft of the conning tower. The guns were rigidly fixed

to the deck and so were in the water whenever the ship submerged;

but all the more delicate parts were covered with a thick coat

of tallow, and as far as I could tell the salt water did little

damage to the guns. Extending up through the top of the conning

tower were two periscopes about twenty feet long which housed

inside, but could be extended at will; so the submarine could

cruise along submerged to a depth of fifteen feet, and at the

same time, by running up a periscope, see everything that happened

on the surface. The submerged speed was eight or nine knots, but

on the surface it was fully sixteen knots. She carried folding

radio masts which were hoisted every night, until one night they

were damaged in a storm and from then on dependence had to be

placed in the aerial stretched between the heavy cables running

from stem to stern over the conning tower. These cables passed

above guns and conning tower in such a way that all projections

on the submarine were protected from nets and the like. At the

stem the cables were made fast to saw-edged steel bars which were

expected to cut the strands of wire whenever a net was encountered.

Right below the conning tower was the control room where there

were always two men on watch and where were controlled all devices

for submerging.

In good weather all the navigating was done from the top of the

conning tower while the steersman was inside the tower; but in

very rough weather the officer of the deck went inside and the

hatch was closed. With the hatch closed the U-boat could submerge

immediately by simply tilting the horizontal rudder. The descent

was very gradual and the submarine, instead of dropping like a

heavy weight, was forced through the water by the propellers at

a very slight incline. With the hatch open it took about ninety

seconds to shift from the internal combustion or Diesel engines

to the storage batteries, close the hatch, and submerge.

Just forward of the control room were two very small compartments,

one to starboard and one to port, with a passage between. The

starboard compartment was used as a cabin by the two youngest

officers. It was probably seven feet long by four feet wide. The

port compartment was somewhat smaller and was used as the radio

room. Forward of these two compartments was the wardroom, about

seven feet long and six feet wide, on one side of which were two

bunks, one over the other, used by two of the officers, and on

the other side a washstand and some lockers built against the

bulkhead in which was kept the wardroom food. A collapsible table

occupied the center of the roon1 and on this our food was placed.

In the evening after the food was put away a hammock was swung

in the center of the room and in this I slept every night I was

aboard.

Forward of the wardroom was the captain's cabin, a room of about

the same size as the former. He had a bunk, a desk, and a chair,

and no place for anything else. Two other compartments were forward

of the cabin: the large sleeping compartment for the crew (in

one corner of which was the officers' toilet) and the forward

torpedo room.

At the stern was the after torpedo room, but these two compartments

I was never allowed to enter. However, I learned that the U-go

carried eight torpedoes. She had sunk two twenty-five-hundred-ton

ships before she torpedoed the President Lincoln. Three torpedoes

were expended on us and one each on the others, so she still had

three left. It was to get an opportunity to fire these remaining

three that Captain Remy stayed two days longer on his cruising

ground after sinking the Lincoln.

Abaft the control room was another large sleeping compartment

for the crew, and here also was the galley where all the food

for both officers and men was prepared. Between this compartment

and the after torpedo room was the engine room with its two Diesel

engines.

Although the quarters were cramped and there were many inconveniences

to be put up with, life aboard was not so unpleasant as people

are likely to imagine. We had only sufficient water for washing

our hands and faces once a day, and the crew had hardly that much.

The submarine rolled considerably in a heavy sea, but when submerged

there was absolutely no sensation of being in motion. The air

in the boat was very good and seldom did it become disagreeable.

Besides "Kapitan-Leutnant" Remy, the commanding officer,

who was a "regular," and who had entered the German

Naval Academy in 1905, there was a young engineer lieutenant who

had graduated from their Engineering School and who was responsible

for the efficient condition of the machinery; a young lieutenant

who had entered the Naval Academy in I9I3; and a reserve lieutenant

who had been in the merchant fleet before the war. Then there

was another officer of the same rank as Remy, who was making the

cruise preparatory to taking command of one of the new submarines

Germany was building.

The crew was composed of young men, happy and in good physical

condition. They seemed to like the duty aboard, but I found out

that the reasons why it was so popular were: first, after about

three round trips they were given the Iron Cross; second, they

had the best food in Germany; third, half the crew were given

leave of absence every time they were in port; and, fourth, they

received the highest rate of pay in the Navy and this was further

increased by a certain sum for each day they submerged. So for

all these reasons the Germans were able to keep their submarines

manned by voluntary enlistments, at least until the last months

of the war.

Captain Remy treated me with extreme consideration and politeness.

He tried to make things as pleasant for me as possible and his

officers took their cue from him. I messed with them at their

little table and took part in the conversation which, for my sake,

was often in English—for nearly all the officers could speak

English fairly well, the " regulars " being required

to study it at the Naval Academy.

We had many sociable evenings, and they helped me to forget for

a few hours at least the trying position in which I found myself.

I had played bridge in English, French, and Spanish, but it was

not until my sojourn on the U-go that I learned to play it in

German. Every evening when the remnants of the last meal were

cleared away we gathered around the little table in the wardroom

and played cards. I was agreeably surprised when one evening after

I had learned how to play a real German game, Captain Remy suggested

that we play bridge. And a very interesting game they made of

it.

We had four meals every day: breakfast at 8 A.M., which consisted

usually of canned sausage ("vorst," as they called it),

canned jam, canned bread, canned lard, and coffee; dinner at twelve

o'clock noon consisting of soup and the rest the same as at breakfast;

"Kaffee" at 4 P.M., which was coffee and bread with

the lard (they called it marmalade) spread over it; and supper

at 8 P.M., when we had potato pancakes, or some such delicacy

of the cook's, together with the same old standbys—sausage,

bread, lard, and coffee.

Occasionally we had tea and a few times cocoa. Twice we had eggs;

but the usual menu was what I have just described. This could

hardly compare with the food of the President Lincoln nor with

the Navy ration; but as Remy warned me, it was decidedly the best

food in Germany and so very much better than I should be likely

to see that he begged me to eat while I had the opportunity. God

knows he spoke the truth.

(Back to

Contents)

|

CHAPTER V

SUBMARINE JOY-RIDING

HAVING sighted so many American ships in those waters, Remy decided

that things were getting too warm for him on his cruising ground,

so he turned northward and began the trip home. He did not try

to run through the Straits of Dover, " for," as he said,

" the English have finally sewed them up," but instead

took the northern route. The weather was fine, and we ran most

of the time on the surface at from eight to ten knots speed. Several

days it was so calm we shipped no water over the deck, so I sat

out in the sunshine and watched the waves roll by.

We zigzagged continually, making sharp turns and large angles

with the base course. For four days we ran along the Irish coast

and northward without sighting a ship, and finally one morning

about four o'clock they awoke me to go hunting.

We were then near the Arctic Circle and being June it was daylight

all night long. When I came on deck I found that we had approached

to within a hundred yards of what looked to be a barren cliff

rising straight out of the water. It was North Rona, one of the

little islands lying west of the Scottish Main, and Remy knew

it as the abode of a few hundred half-wild sheep —for he

had been there before. He told me that years before a hermit had

come to live on the island and had begun the raising of sheep.

When he died the sheep continued to thrive. From my position on

deck I could count about one hundred and fifty, but I got no closer,

for when the little bateau was brought out from its place between

the inner and outer hulls and an officer and two men with their

guns had taken their places in it as it lay alongside the ship,

the captain decided it would be better for me to stay aboard.

My binoculars had not been taken from me, so through them I watched

the "sport." The boat pulled up to a small inlet where

the occupants were able to make a landing. They tied up the boat

and the three of them climbed up the rocks to a grassy plain in

the center of the island. Then they drove a large number of the

sheep up to the top of the cliff on the west side of the island

and proceeded to shoot nine of them. One little woolly lamb they

caught alive and brought back aboard. We named it Rona, and from

that time on Rona and I, being companions in misery, were the

best of friends. One of the sheep they shot fell over the side

of the cliff into the water. Remy slowly backed the submarine

to within three feet of the base of the cliff, where a sailor

with a grapnel reached over the stern and caught it up. When the

hunting party returned the sheep were dressed on the deck of the

submarine by the ship's cook and every day thereafter we had fresh

mutton.

Proceeding on our way we rounded the Shetlands and headed south

into the North Sea. I had now been aboard a week and already had

collected some information. I glanced at the charts whenever I

had an opportunity; I also borrowed an atlas from one of the officers.

In this way I learned as much as I could about our course and

the habits of the U-boats.

We ran down the coast of Norway, then across to the Jutland coast

through the Skaggerack and into the Cattegat. One night in the

North Sea we met another German submarine that was short of oil.

The captain came aboard, talked awhile with Remy, and then returned

to his ship lying a few hundred yards away. He decided it was

too rough to take oil and said he would try to make it to Kiel

with what he had. Two nights later in the Cattegat we had another

meeting with him, and this time he asked Remy for enough oil to

make sure of an adequate supply for the run to Kiel. The two submarines

had exchanged recognition signals and approached. The oil was

then pumped through a hose from the U-90 to the other submarine.

This took about an hour, and we then continued the cruise.

The following day, June 9th, we ran on the surface until 9 A.M.,

and then submerged and rested on the bottom in water less than

a hundred feet deep. We stayed there a short time and then came

to the surface. At noon we submerged again, this time to a depth

of over two hundred and twenty-five feet, and at five knots speed

approached The Sound, the narrow waters lying between Denmark

and Sweden. Great care was taken to avoid the mine fields which

are strewn through the Cattegat. We remained submerged more than

ten hours, coming to the surface at II P.M. The air was rather

disagreeable toward the last, but not unbearable. Several tanks

of oxygen were carried to replenish the supply of fresh air whenever

it became necessary.

When we came to the surface at eleven o'clock all the officers

including myself went up on deck for a smoke. It was barely dusk,

for in those latitudes and at that time of year there is practically

no night, or at least no real darkness. I found that we were in

a small bay with the lights of Sweden on one side, the lights

of Denmark on the other. We were probably four miles from land.

A few minutes later another submarine came to the surface about

a quarter of a mile away, and then another. The three of us slowly

cruised up and down in the middle of the bay for perhaps an hour.

It had become a little darker. Suddenly I resolved on a break

for liberty.

Many times during my stay on board the submarine I had planned

to escape. I racked my brain for ideas. I searched the ship for

"escape material." I ransacked the drug locker in my

efforts to find something to aid me in either capturing the submarine

or taking my leave of it. On the plea of wanting to clean my pistol

I got it back again. I cleaned, oiled, and loaded it, and not

to arouse suspicion, I put it on the captain's desk, where, however,

I could get it at any time—but I had only twenty cartridges

and my captors numbered forty-seven. The odds surely seemed against

me. At last, however, I felt that the long-awaited opportunity

had arrived.

My lifejacket had never been taken from me, and with that on I

was sure I could swim to the shore, or at least remain afloat

until picked up by one of the little fishing boats common in those

waters. But it was still too light for the attempt, and it would

be worse than useless to get into the water and then have the

submarine pick me up again, which would surely happen unless I

could lose myself in the darkness.

I waited until twelve-thirty, and although it was not so dark

as I would have liked I decided the time had-come. Just about

this time a German destroyer bore down upon us from the eastward

making high speed. She was undoubtedly keeping the rendezvous

for the purpose of escorting us through Danish waters into the

Baltic. I was now sure that I knew their rendezvous and I could

trace again their course, if only I could get back with my information.

I casually wandered over to the edge of the deck and made ready

to jump. Just as I was going over the side Remy, who had never

been far from me, caught me by the arm. Resistance was useless.

He ordered me below, but before I passed through the conning-tower

hatch, I took one last look around and saw that the destroyer

was placing herself at the head of the column of submarines and

heading west toward the channel into which I had seen several

small fishing boats disappear earlier in the evening. I am sure

in that direction lay Copenhagen—perhaps not far distant.

The following morning I arose early and was allowed to go up on

deck. I feel positive Remy never held against me my attempt to

escape, and to this day has not reported it. I found we were in

the Baltic and our companions of the night before were nowhere

to be seen. It was a beautiful day and the water was like glass.

I sat down on deck with my binoculars and viewed my surroundings.

There was great activity on the U-90. Breech-blocks were being

taken out of the guns and cleaned; the "bright work"

was being polished, and all preparations were being made to enter

port. This was June 10th, the eleventh day of my enforced visit

aboard. Three or four merchantmen flying the German flag passed

us going east. Later in the morning, near Fehmarn Island, which

lies north of Lubeck, we passed the battle cruiser Hindenburg

and two other battle cruisers of the same type. Farther on were

four smaller cruisers maneuvering individually.

We continued past Fehmarn to Kiel, where we arrived and tied up

to the landing at the entrance to the locks at 3 P.M. There was

a net across the entrance to the harbor, and outside we passed

six or seven small destroyers and four or five submarines. The

latter were probably on practice trips. Inside the harbor there

were seven seaplanes engaged in making landings near the bathing

beach, where many women and children played in the chilly water.

On the other side of the harbor from us were two of the new submarine

mine-layers. They mounted a six-inch gun forward and looked to

be about three hundred and fifty feet long. They appeared to be

still in the "shaking down" stage. In the government

docks farther down I could see about ten light and armored cruisers

looking real new in their coats of fresh paint.

One of the officers took me ashore for a short walk after I had

rid myself of the two

weeks' growth of beard with the aid of Remy's razor. I saw little

of the town and was soon back aboard. At 7 P.M. we shoved off,

entered the locks, and then proceeded down the famous canal at

nine knots speed. Another submarine followed us, and Remy told

me it was the one that torpedoed the Celtic and the Tuscania.

I stayed up on deck until after midnight and made mental notes

of the canal. It is rather narrow except in a few places where

it has been widened to allow of the passing of large ships. The

shores are cemented part-way up the slope, and it is in every

respect neat and clean. Every hundred meters there is a bollard

to which ships may tie, and powerful electric lights are hung

at frequent intervals making the canal at night-time almost as

light as day. The shores at the top of the slope are patrolled

by sentries, and every few kilometers there is a small ferry and

a guardhouse filled with soldiers. A very few bridges, and these

with high arches, span the canal.

When I awoke the following day we were in Heligoland Bight, heading

south toward the mouth of the Jade River, up which a few miles

is Wilhelmshaven, the base of the High Seas Fleet. Overhead at

a height of about two thousand meters patrolled a huge Zeppelin.

Repair ships, small destroyers, and thgs were everywhere. A division

of three battleships, of which two were the Kong II and the Grosser

Kurfurst, passed us at high speed heading north and escorted by

a division of four large destroyers. We entered the locks at 10

A.M. and after passing through went alongside the "mother"

ship Preussen. My joy-ride was over.

(Back to

Contents)

|

CHAPTER VI

IN WILHELMSHAVEN

THE old battleship Preussen, now dismantled, small destroyers,

and used only as the "mother" ship for six or eight

submarines, lay in a backwater from which none of the city could

be seen. When the U-90 had tied up, I was sent aboard and was

immediately placed in a room with a barred port, the door was

locked, and an armed sentry took up his post outside. The commanding

officer of the Preussen came to the room later and I asked for

a toothbrush, a comb, and permission to take a bath. A few minutes

later he returned with a new toothbrush and a broken comb. I saw

him no more, and he apparently left my entertainment to my guards.

Later in the day I prevailed on the guard to let me take a bath.

He took me to a sort

of laundry, and there in a tin tub I finally got clean again.

That noon I had had a plate of soup and a large piece of sour

black bread. I could not eat the sour dough on the inside of the

loaf, and the crust which enclosed it was over half an inch thick

and as hard as a rock. I tried to chew that, but broke one of

my teeth on it, so decided that further attacks would be useless.

" Anyway," I consoled myself, " this is the small

meal of the day and I will have a genuine repast to-night."

About five-thirty that evening my guard brought me a cup of colored

water —hot and with some dregs in the bottom. I tasted it

and found that it was nothing more nor less than plain hot water.

It just did not "taste," that was all. I waited for

supper or dinner or anything else they cared to bring me, but

as nothing materialized I grew sleepy and went to bed. My room

contained, besides the bed, a washstand, a table, and a chair.

In the morning I was up early and ready for a mammoth breakfast.

At eight o'clock my guard brought me a cup of "warm Kaffee,"

as he said. I thought I had better drink it at once before it

got cold instead of waiting for the rest of my breakfast. But

one taste was enough. The night before I had made the acquaintance

of "ersatz" tea made out of strawberry leaves which

at least had the redeeming virtue of being tasteless. Now I was

face to face with friend "ersatz" coffee made out of

burnt acorns and barley, which, however, could not boast of any

virtue, and the taste was so bitter that even quinine would have

been far preferable. Of course, had there been sugar and cream

I might have been able to drink it, but it was sacrilege even

to mention those luxuries. Well, that was my ration. No more breakfast

came, and at noontime the same routine began again.

I used to look out of my barred port (about ten inches in diameter)

and see the ship's crew carrying their food from the galley to

their messing quarters. I was an officer, but could I have had

even the food the crew was eating, which was infinitely better

than what they gave me, I should have been perfectly satisfied.

Of course, had I been a German naval officer on an American man-o'-war

I should have been messing deluxe in the wardroom and being treated

with all the courtesy and consideration due my rank—in fact,

as an equal. Yes, even had I been guilty of the murder of innocent

women and children I should have been treated as the officers

of the U-58 were treated by the officers of the American destroyer

Fanning when the U-58 was damaged and forced to surrender. But

being an American officer on a German man-o'-war, I was locked

in a small room in solitary confinement with nothing to read,

and given food we should have been ashamed to feed an animal.

Captain Remy, of the U-90, came in to see me once before he went

on leave. I had found a five-dollar bill in my pocket, which was

everything I had in the world after the ship went down, and this

I asked Remy to change for me into German money, which he kindly

did, also buying me some toothpaste and toilet articles. The officer

who was on the U-go for training purposes also came in to see

me in my prison room. He came to say good-bye, for he had just

received orders to proceed to Kiel and take command of-one of

the new submarines. It was then that I first realized the un-German

character of the treatment I had received on the U-90. While there,

all the officers had tried to make things pleasant for me, and

although we had many arguments on the war the discussions were

friendly. I could not help contrasting this with my treatment

on the Preussen.

The second day of my stay on the "mother" ship, a young

officer came to take me to the Wilhelm II, flagship of the High

Seas Fleet. We entered a waiting launch and shoved off, passing

by several docks where ships of all kinds were tied up. I counted

fully twenty-five destroyers apparently with no steam up, but

partially manned, also six or seven battleships and a few cruisers.

When we arrived alongside the Wilhelm II, I noticed that she was

partially dismantled and had her upper works enclosed in sheet-metal

to form temporary quarters. She was merely the port flagship I

learned, and a new superdreadnought was used as the seagoing flagship.

I was taken to a room marked "Chief of Staff," and there

met an officer who spoke perfect English, having lived twelve

years in England, as he told me. He began by being very courteous

and talked about everything except the war. Then he commenced

asking questions and tried to get information about our Navy and

what it was doing, and also about the Army—how many troops

we had in France and how many we were sending over every month.

I rather frightened him with the tales I told of the two million

men we had in France and the twenty million more who were on the

way, until finally he lost his temper and demanded to know why

America had entered the war: that it was none of her affair, and

that it was all bosh to talk about "making the world safe

for Democracy" and other altruistic motives, since no nation

ever went to war except for gain; and the only reason why America

could have possibly entered the war-was to safeguard the millions

she had loaned to England and France.

"Why!" he exclaimed, "we expected you to come in

on the side of Germany."

Now all this was old news to me, for it had been the argument

of all the officers on the U-90, and I recognized it as the propaganda

issued by the Government which is taken as the absolute truth

by every German high and low. It finds an echo from the lips of

every one of them—they all read the newspapers—for with

practically not an exception I heard these same ideas expressed

by each German I met during my stay in Germany.

Needless to say the Chief of Staff and I no longer agreed. It

took me but a short time to set him aright as to America's reasons

for entering the war.

"Do you think America will ever forget the Lusitania?"

I asked him; "or ally herself with the authors of the famous

'Hymn of Hate'?"

And then, with the most biting sarcasm of which I was capable:

"But then even had we joined with you we could not have.

entered the alliance on an equal footing. We had nothing to offer.

We had no reputation established in the realms of pillage and

rapine. We had not murdered any women and children. We were not

even Huns!"

Whereupon the interview ended. I had heard, and I have since proved

to my own satisfaction, that the most scathing remark one can

make to an educated German is to call him a "Hun."

Another day of my solitary confinement on board the Preussen,

and then about dusk a warrant officer and four armed enlisted

men escorted me through the streets of Wilhelmshaven for three

miles to the Commandatur—a group of buildings surrounded

by a high stone wall. Here I was placed in a small room opening

off a corridor. A guard with a loaded rifle was outside my window.

Another stood in the corridor outside my door which was kept locked.

The prison building itself was locked and the place was full of

jailers. The adjoining buildings were barracks for sailors and

recruits; and the courtyard in the center was patrolled by several

guards. I thought of escaping, but I knew that even were I able

to get out of the Commandatur, which was practically impossible,

I could never get out of Wilhelmshaven, the most intensely guarded

city of Germany.

At the prison I was searched and my identification disk taken

from me. I was given the same kind of food (?) I had received

on the Preussen. Fortunately I was there only parts of three days,

so I was not quite starved—but I lived an eternity in that

short time.

About 4 A.M. the morning of my third day at the Commandatur, I

was called and told to be ready by five o'clock to leave the prison.

Exactly at five an officer and two sailors came for me and I was

marched to the station and on the train for Karlsrnhe. We went

by way of Hannover and Frankfort-on-the-Main.

Outside of Wilhelmshaven I saw large herds of cattle apparently

for the Fleet. These were the only cattle I ever saw in Germany.

It was haying-time, and through the fields were scattered women

and children (even infants) and old men. Occasionally I saw a

prisoner helping and sometimes a German soldier. There was some

grain growing, but very little. I came to the conclusion that

the soil was so poor nothing but hay would grow.

In passing through the large cities there were many people at

the stations, but although the German armies were advancing in

France, nothing but sorrow could be seen in their countenances

and there was a certain lack of noise and activity that was appalling.

Of course I had had no breakfast and by noontime I was nearly

famished. It was then that we arrived at Hannover where we changed

trains. I noticed the young officer go out and apparently get

dinner in the station cafe. I waited to see if there was any food

forthcoming for the prisoner, but nothing appeared. Finally I

asked if any arrangements had been made for my entertainment besides

the free ride on the train. He must have understood, because he

countered with " Have you any money ? " I remembered

the remainder of my former five-dollar bill. I had several marks

left, so I told him if he could arrange a modest meal the contents

of my pocket were his. With this incentive he quickly accomplished

the impossible. I had some potatoes and string beans and a very

tiny piece of meat. But no banquet could ever compare with that

meal.

About dusk we arrived at Karlsruhe where the officer and his men

turned me over to the Army authorities.

(Back to Contents)

|

CHAPTER VII

THE LISTENING HOTEL

NOT far from the station of Karlsruhe there is a hotel which before

the war was probably like any other of the thousands of cheap

hotels in Germany. Now, however, it had been taken over by the

Government and all the rooms stripped of everything-they formerly

possessed. The windows had been frosted over and locked, and for

furniture they had placed several beds of shavings, stools, and

tables in each room. It was to this hotel I was taken by the Navy

guard and was immediately placed in one of the rooms alone.

The next morning a British warrant officer was placed in the same

room with me. Here they made no pretense of giving us breakfast.

We had nothing until noontime when we were greeted with soup and

a plate of black, frost-bitten potatoes. After "dinner"

I was ordered down to the intelligence office on the ground floor

where I was interrogated by a German Army officer—I had seen

my last of the Navy.

The intelligence officer asked me questions from a typewritten

sheet and I saw him covertly write in the answers. "How many

troops in France?" "Two million, and twenty million

more ready to come." "How long will the war last?"

"At least five years."—That always hurt their feelings

terribly. They were always hoping for peace in a few months, and

every German would say, "Oh, yes; the Allies cannot hold

out more than two months longer."

Four months later the common people were still being fed the same

propaganda —each month was to see the end of the war—but

when it did not end what did they do: lose confidence in the Government?

No, indeed! They would go on believing forever if the Kaiser or

any one in authority told them to. I could see some hope of the

people rising up and demanding a change—but it was to be

by the few leaders such as Liebknecht, Erzberger, Scheidemann,

and the like; never the mass of the people themselves.

When this officer had received my answers to his questions, I

was sent back to a room, but not to the same room from which I

had come. Here I found seven Frenchmen. They made me welcome and

we sat around and talked in French. They had been captured at

different points of the front and all had interesting stories

to tell. As the day wore on one of them who was so fortunate as

to have a razor decided to shave himself. There was a small cracked

mirror on the wall which he took down to place in the light. As

he did so, one of the others noticed that the wall where the mirror

had been hanging was scratched as if with a sharp instrument and

upon approaching closer he deciphered the following:

"Beware of the dictaphones." Investigating further,

we found the same warning in all the Allied languages, sometimes

scratched in the plaster of the wall and sometimes written in

pencil on the under side of tables, chairs, and bunks. That day

for our supper we were given the same kind of soup as at noon

and this completed the day's refreshments.

The following day I was sent to a room where there were three

British officers, and in this room a search revealed the same

warning. While I was at the "hotel" three dictaphones

were found by the officers. They tore them out and destroyed them.

I am sure the Germans gained very little information from us,

but they undoubtedly learned a few of the many choice ways in

which we habitually spoke of our "friends," the "Huns."

By comparing the stories of other officers, whom I met in the

prison camps to which I was afterwards sent, I learned how the

system works. Ordinarily an incoming prisoner is placed in a room

alone. He stays there for a day or two and is sent to the intelligence

officer, who plies him with questions. If he refuses to answer,

or is otherwise obstreperous, he is sent back to his solitary

confinement. When it is considered that he has been alone long

enough and will be anxious to talk with the first person he meets,

he is placed in a room with officers who speak the same language

and are, like him, prisoners. By means of the dictaphones it is

hoped to obtain information of value which one is likely to let

fall in his eagerness to talk again. Sometimes the officers he

is placed with are spies, but this is not resorted to now as much

as at the beginning of the war, owing to the prevalence among

prisoners of the idea that all "companions" are enemies.

The fourth day at the "hotel" the British officers

in my room were sent away to the prison camp. I endured the solitude

for a few hours and then asked to see the intelligence officer.

When he came I asked why I was undergoing solitary confinement,

and why it was being drawn out so long. He assured me that I should

that day be sent to the camp which was only a few blocks away.

Accordingly, a few minutes later, the guard lined up outside the

hotel and I was escorted through the streets to the Zoological

Gardens

(Back to

Contents)

|

|

CHAPTER VIII

THE CAMP

ABOUT the second year of the war, while Hagenback's Circus was

playing in the Zoological Gardens at Karlsruhe, a British aeroplane

squadron came over and dropped bombs on the city, one of which

fell in the midst of the people who were attending the performance.

Several hundred people were killed or wounded. In retaliation

the Germans built a prison camp at the scene of the disaster,

planning this as a safeguard against further bombing. As a matter

of fact, the railway station a few blocks away from the camp was

bombed by the Allies' aero squadrons on an average of two or three

times a week, but no bombs ever fell near the camp.

When I entered the camp I found a group of wooden shacks in the

shape of an irregular polygon with a court in the center and surrounded

by three fences. The inner fence was of wire only seven feet high,

but the middle fence was of boards surmounted by barbed wire to

a height of twelve feet. The outer fence was of wire like the

inner and in certain places there was a fourth fence outside similar

to the two just mentioned. The distance between the fences was

perhaps eight feet. Inside the court there were five armed sentries

constantly patrolling and outside the last fence a line of sentries

spaced about thirty yards apart who had more or less stationary

posts. The whole camp occupied a site about half as large as a

city block.

I was taken to one of the shacks where I was searched and everything

except my clothes taken from me—even my binoculars. In the

pockets of my trousers and blouse which I was wearing when the

President Lincoln was torpedoed, I had a few religious articles,

a bunch of keys, and some letters. All went as contraband. When

the search was finished, I was sent to another hut where I found

seven Frenchmen and eight beds. This was to be my home.

The building was constructed very much like a barn. Partitions

divided it into four rooms in each of which were eight beds of

wood shavings, eight small stools, and a table. When I had made

the acquaintance of the Frenchmen I went out into the court and

there found many British officers, several of whom were Canadians,

waiting to greet me. I was the only American. The Germans were

still advancing in France, but were those British lads downhearted

? Decidedly no! As they shook hands with me (I noticed that nearly

all were wounded), they wanted to know just one thing: "America,

are you with us?" Fortunately I could assure them that America

was with them to the end. They did not propose to give up the

fight until the Huns were whipped, they said, but they knew America

would have to see the thing through with them or they could not

win. France had already given her all.

There were about one hundred British, sixty French, fifteen Italian,

and five Serbian officers at the camp when I arrived, but the

number fluctuated. All the Allied officers were first sent to

the "listening hotel" at Karlsruhe which was the headquarters

of the intelligence department. Then, while awaiting transfer

to the permanent camps throughout Germany, they were temporarily

placed in the camp in the center of the Zoological Gardens. I

was there three weeks, and in that time saw two or three times

the capacity of the camp arrive and depart. Some, however, stayed

months and others came in one day and left the next. There seemed

to be no intelligent system followed in transferring prisoners:

at least I came to this conclusion after seeing several prisoners

shifted from one end of Germany to the other for no apparent reason.

After becoming acquainted with the British officers I met most

of the French. They had a committee which was in charge of all

the food the French Red Cross sent to the camp, and the chairman

of the committee took me under his wing, saying he had orders

from France to take care of any Americans who should come through.

They had very few supplies, but I was treated like one of their

own and given whatever they had. Among the first things they gave

me were a few very necessary articles of clothing. They also had

some dried beans on hand, a little coffee— real coffee—and

some hard biscuits. The French hard biscuits have saved many lives

in this war. We used to cut a hole in them, pour in water, and

soon they would swell up, become soft, and closely resemble white

bread.

I quickly became accustomed to life in the camp. We had no breakfast.

At noontime we had a plate of soup made out of leaves. This was

followed usually by a plate of black potatoes (the good potatoes

were saved for the German Army) or horse carrots or some similar

vegetable. At 6 P.M. we had another plate of soup and sometimes

there was dessert: a teaspoonful of jam. It was terrible tasting

stuff and for a long time we could not tell what it was made of;

but a few months later we saw peasants gathering the red berries

of the mountain ash and they told us they made them into jam.

That accounted for the taste.

That was our ration from the Germans with the exception of the

black bread. Once a day we were given a piece of this bread about

as big as a man's fist. It weighed about two hundred and forty

or two hundred and fifty grams. Now half a pound of white bread

makes a relatively large bulk; but the small size of this half

pound is easily understood when I describe the ingredients. We

tried to analyze it one day and this is what we found: first,

water and potatoes; second, sawdust and chaff; and third, sand.

As for the soup, in all the time I was there it was never changed.

It looked and tasted like water; and the leaves with which it

was filled were, of course, not edible. Were it not for the food

I obtained from the French committee I should never have lasted

out those three long weeks.

The canteen sold cider and so-called wine, and once in a while

some dried fish. No other foodstuffs could we buy. They had safety

matches for twenty-five cents a small box, "ersatz"

cigarettes and tobacco at exorbitant prices, the ten-cent variety

of granite-ware plates and utensils for from one to three dollars

each, oil-cloth at seven dollars per yard, and a few other articles

that I have forgotten. They told me that the tobacco must contain

seventy-five per cent of hops, by order of the Government. It

looked like wheat chaff, but we bought it just the same, rather

than have nothing to smoke.

Our orderlies were British "Tommies" and French "Poilus."

Some had been captured at the beginning of the war, others more

recently. My little "Tommy," to whom I became greatly

attached, used to tell me about his home in "Blighty,"

and how much longer he would have to wait to see it. One day he

told me how he was taken. His battalion was cut to pieces and

the remnants captured. After terrible hardships they found themselves

in the rear of the German lines. They were then lined up and counted.

Three officers and less than a hundred men were left. The officers

were ordered to step to the front, and there before the eyes of

their men they were shot down in cold blood. I cite this, not

as anything extraordinary, but as a sample of the tales told by

officers and men alike, who, knowing that land warfare was new

to me, a Navy man, used to recount their experiences and then

ask to hear mine.

One day six or seven "Tommies" came to the camp to replenish

the supply of orderlies. I was near the gate as they came in,

and of all the terrible sights I have ever witnessed that was

the worst. The poor lads were absolutely skin and bones: I called

them walking skeletons. They came in dragging their feet along

and were so weak they could hardly stand. They had no shoes nor

stockings, but instead had some rags tied around their feet. In

fact the only clothing they had consisted of ragged trousers,

and a few strips passed over their shoulders and tied to the tops

of the trousers.

I learned their story. Since their capture they had been held

at St. Quentin, where, although the Germans had accepted the terms

of the agreement whereby all prisoners of war were to be kept

at least thirty kilometers behind the firing line, they were forced

to repair roads under the fre of their own batteries. Their food

was only one plate of soup a day. Some of the officers who had

just come in assured me that they had seen these same lads a few

mornings before under their prison windows at St. Quentin waiting

for it to become light enough so they could search the ground

for crusts of bread, cigarette stubs, or anything else the officers

might have discarded the night before.

(Back to

Contents)

|

CHAPTER IX

PLANS OF ESCAPE

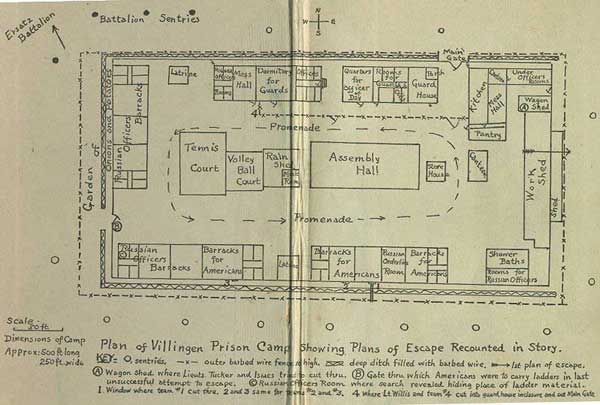

I HAD been at Karlsrnhe but a few hours when I made a tour of

the camp and sized up my chances of escape. Realizing my ignorance

of the subject and knowing I could get good advice from the other

prisoners, I let them know I had information which I was anxious

to get back to the Navy and that I proposed to escape at the first

opportunity, or failing an opportunity that I intended to make

one. The British and French officers immediately offered me money

and food, maps and a compass.

Karlsrnhe is about one hundred miles from the Swiss frontier.

A good map was almost a necessity and the compass would be my

only guide in the long night marches. The trip would take at least

fifteen days and food to last that long would be difficult to

escape with. But with concentrated food, such as sweet chocolate,

loaf sugar, and French biscuits, a very little would keep a man

going indefinitely.- Those of the officers who had been taken

prisoner a long time before were receiving food of all kinds from

home; and from them I got what I needed.

Money would buy many things. In an emergency, a hundred-mark note

dangled before a guard's eyes would probably mean the difference

between recapture and freedom. Of course I had no money, but I

knew that I was entitled to some, so I asked for an interview

with the commandant, got it, and told him that in my understanding

of international law I was entitled to at least a part of my salary

as an officer of the United States Navy. He informed me that his

Government had no agreement with America and therefore he had

no authority to pay me. When he heard, however, that I had no

money at all, he agreed to pay me the same as the British officers

with whose Government there was an agreement. The lieutenants

were paid sixty marks a month and the captains and above, one

hundred marks.

So he ordered the paymaster to give me one hundred marks, since

my rank corresponded to that of an Army captain. Then the paymaster

deducted sixty marks for my "board" and gave me the

balance. This money was never paid in good specie, but always

in the form of camp paper money, good only inside the camp, at

the canteen, and for similar purposes.

I could hardly hope to buy my way to freedom with forty marks,

but several of the officers were able to secrete good French,

German, and British money in their clothes in such a way that

it escaped detection in the search which every one had to undergo

when entering or leaving a camp. One French major came in with

twelve hundred francs in good money and hearing my plans he came

right over and handed it all to me.

Among my fellow prisoners were several who like me wanted to

escape. We talked over the many plans that had been tried since

the beginning of the war, and in this manner I learned what to

do and what not to do. Allying myself with two French aviators

and some British officer prisoners, I planned my first Karlsruhe

escape.

Working at night we were able to loosen some staples that held

the wires of the inner fence to the posts. In this way we made

an opening large enough to pass through, and then quietly attacked

the board fence. It took several nights of painful work with the

sentries only a short distance away, but finally we had one board

loosened in such a way that a single wrench would tear it off.

By judicious use of money and French biscuits we had acquired

two friends among the sentries—one of whom was a young Swiss

boy who had run away from Switzerland and been impressed into

service by the Germans. Through him one of the French aviators

communicated with friends he had met in Karlsrnhe before the war.

One of these, his fiancee, a German girl, was preparing her basement

for us to live in for a few days after we should escape from the

camp and while the search was still hot. Then, when the uproar

should have died down, we would crawl out under cover of darkness

and begin the march to the frontier.

For sentimental reasons I chose the 4th of July as the day for

the attempt. When the sentries on the inside of the camp were

properly disposed, we were all to slip through the inner fence

and line up near the loosened board, the first man was to wrench

it off and go through, and the rest were to follow. Then we were

to storm the outer wire fence and climb over, feeling sure that

the size of our party would so frighten the guards that they would

be unable to fire until we were safe behind a row of trees and

bushes which grew only fifty yards from the camp. After that it

would simply be a case of running through the town to the forest

beyond. On the way four of us would drop out and make our way

to the basement mentioned before. The others would divide up into

twos and threes and scatter.

All plans were completed, our food, maps, and compasses assembled,

and all was in readiness by the morning of July 3d. The last letter

to friends in town had been given to the Swiss guard and we waited

only for the darkness of midnight. As the guards were relieved

at rr A.M. I noticed a commotion of some kind at the main gate.

Hastening over I saw that our guard had been searched and the

letter found in his clothes. Things happened rapidly then. The

young aviator who had written the letter was sent for, but he

refused to tell the names of the rest of us. The commandant immediately

telegraphed to Berlin asking for instructions and the guard was

doubled both inside and outside of the yard. Of course that plan

was ruined, but we did not lose hope.

The next day was the 4th of July and we celebrated as best we

could. Five American aviators had just come in and with them I

observed the Day. We collected as much food as we could find,

except, of course, the reserve for escape purposes, which was

never touched no matter how hard-pressed we were. One of the aviators

had brought in a tiny silk " Stars and Stripes," and

with this waving over the table we had our banquet.

The next morning orders came from Berlin to clear the camp of

all officers. That day nearly all the French and British officers

were sent to camps in Northern Germany. Two British generals,

some Serbian and Italian officers, a few French aviators, and

I were left. With one of the aviators I planned to get away that

night.

In one corner of the camp there was a large tree which had very

thick foliage and one limb of which extended out over the three

fences. I conceived the idea of climbing the tree before "Taps,"

which was at eleven o'clock, hiding in the foliage until about

1.30 A.M., then crawling out to the end of the big limb, making

fast a line, and sliding down outside. A scheme similar to this

had been planned a few nights before by one of the American aviators

and myself, but we were unable to climb the tree before "Taps"

sounded and the sentries ordered us inside our barracks.

I had some trouble in getting a line which would hold our weight,

but after searching the camp thoroughly I finally found an electric

wire in the little theater which the prisoners had built years

before in the center of the camp. This wire was heavily insulated,

and upon testing it we found that it would hold our weight.

That night after dark we placed our reserve food in knapsacks,

made from pieces of an old shirt, and strapped them to our backs.

I wrapped the electric wire around my body, and then, draping

blankets about our shoulders in the manner of German officers

with their cloaks, we donned caps furnished by some of the other

officers and left the barracks. This disguise would aid us after

we were outside the camp and in getting out of the city. We walked

directly to the tree, found the coast clear, and climbed up. Soon

the sentry in that part of the yard walked over and took up his

position directly under us. He was relieved at eleven o'clock

and the next sentry never moved out of his tracks. He in turn

was relieved at I A.M. and the latter again at 3 A.M., but for

some unknown reason they all refused to leave that spot. We could

not move for fear of making a noise.

It was cold and we were terribly cramped; and it was not until

after sunrise that we were able to climb down and mingle unnoticed

with the other officers inside the yard.

(Back to

Contents)

|

CHAPTER X

THE BEST EFFORT

A FEW mornings later I was awakened by an interpreter at six o'clock

and told to be ready to leave the camp in half an hour. Rising

hastily I dressed and then looked around for some way of hiding

my compass, money, and maps. The food would excite no suspicion;

but I knew I should be searched for contraband articles, as was

customary, and that, unless I could secrete these things in a

way that no one else had ever tried, they would surely be found.

I had a jar of lard that the French committee had given me, and

in this I placed my compass. My money I put in a jar of shaving-cream.

For my maps only could I find no hiding-place. I had several detailed

accounts of how French officers had escaped—their itineraries

with notes and plans—which had been smuggled back in loaves

of bread and bars of soap and in other innocent-looking packages.

But all of these I had to destroy. I put my faith in one large

general map, and finally hid it in a box of cocoa that a British

officer had given me. I took out the paper lining of the box and

placed my map folded to the correct size inside. I then dusted

some cocoa over it and replaced the lining which, bag shaped,

contained the rest of the cocoa. Then with my knapsack full of

food I reported to the Mess Hall.

I was told to take off my clothes. One interpreter searched my

knapsack while another went through my clothing. The latter took

each garment separately, kneaded it between his fingers, listening

the while for the rustle of paper, turned it inside out, and finally

cut open the seams in places where it looked suspicious. Even

my insignia and gold stripes were cut open, but of course nothing

was found.

But in the meantime the contents of the knapsack were having troubles

of their own. As soon as the interpreter espied the jar of lard

he reached for it. I was ahead of him, and talking volubly, I

thrust my finger in the jar on the side away from the compass,

showing him it was only lard, and explaining that I was taking

it to the next camp because I did not know if I should find any

there—and, of course, it was very valuable, there being so

little in Germany, etc., etc. I talked in this strain until he

reached for something else. Soon he came to the box of cocoa.

With a long steel needle he began feeling inside. I took this

opportunity to slide the jar of shaving cream back into the knapsack;

and then, as beads of perspiration slowly gathered on my brow,

I watched and prayed that he would overlook the map. After what

seemed centuries to me he made one final jab with his needle and

put the box down. I had won the first skirmish.

When the search was finished I was marched by two guards to the

railroad station. On the way out of the camp I noticed that the

Serbian officers and some Frenchmen who had come in during the

night were lining up to be also marched away. There were about

thirty of them and they had four guards. A lone American usually

had two. We arrived at the station and boarded a train, and then

the guards told me we were bound for Villingen in the Schwarzwald—or

Black Forest, as we call it.

I was unfortunate in having to travel in the daytime, for at Karlsruhe

we had always considered a passage on the train the best time

for making an attempt to escape, provided the traveling was done

at night. The darkness would render it next to impossible for

the guards to find a person if he jumped from the train, even

though he might be wounded. Of course I did not want to force

the hand of Fate, but it seemed that most of the opportunities

had been closed against me up to this time and Fate therefore

needed a little moral persuasion to open up those doors to me.

So I planned to jump from the train when the time looked propitious,

but preferably when we had reached the point nearest the Swiss

frontier.

All the way down to Offenburg, which we reached about noontime,

the guards watched me like hawks. There we changed trains; and

leaving the main line behind, our train headed southward up into

the mountains. We were in a fourth-class carriage filled with

German soldiers back from the front on furlough, who obstructed

the passageway in the center of the coach and thronged around

the door. Little wooden benches about three feet long jutted out

from both sides of the car toward the center.. On one of these

I set with one guard beside me, the other on the next bench facing

me. Each held his gun pointed toward me and I took pains to see

that the guns were loaded.

About two o'clock in the afternoon we reached a place called Sommerau,

where I noticed an engine was switched back. Then we made higher

speed, and of a sudden I realized what had happened. Up to this

time we had been making only ten or twelve miles an hour and were

on the upgrade. At Sommerau we reached the crest of the mountains

and from then on were on the downgrade. Had I known this before

I should have taken my chances with the low speed, but it was

now too late.

At three o'clock we were nearing Villingen. The train was making

about forty miles an hour and we were passing through a valley

which was rather thickly populated. The guns of the guards were

still pointed toward me and they did look ugly; but the window

near our seat was open and I was sure that I could reach it at

a bound, so if they fired they would be just as likely to hit

one of the other passengers as me. It was warm and close in the

carriage and one of the guards was dozing. I waited until the

other slightly turned his head to answer a question put by one

of the soldiers with whom he had been talking. Then, jumping up,

with my knapsack hanging from my neck, I leaped past both guards

and tried to dive through the window. It was small, probably eighteen

inches wide and twenty-four inches high; and as there was nothing

on the outside of the car to hold to, I had to depend on my momentum

and the weight of my head and shoulders to carry the rest of my

body along. My head and shoulders went through nicely; and then

with the shouts of the guards ringing in my ears I simply fell

and all went dark.

(Back to Contents)

|

CHAPTER XI

PUNISHMENT

WHEN I disappeared from view the guards must have pulled the bell-rope,

for the train came to a stop about three hundred yards farther

along. In the meantime I had landed on the track that paralleled

the one on which the train was running. The bed was of crushed

rock and the ties of steel. My head struck one tie and I was stunned,

but rolled over and over; and the shaking up must have brought

me again to my senses, for by the time the train had stopped I

was struggling to my feet.

Then I made a terrible discovery: my knees had apparently struck

the tie next to the one that damaged my head, and when I tried

to run I found they were so cut and bruised that I could not bend

them. My feet, too, had been cut across the insteps, my body was

all bruised, and my hands and arms had small pieces of rock ground

in; but in spite of all this no bones were broken. Had it not

been for the condition of my knees I should have been able to

make my escape; but by the time I was on my feet trying to shuffle

away, the guards had descended from the train and were rapidly

advancing toward me firing as they came.

I tried to run, but could make very little headway, and soon

I was exhausted. My breath came in gasps and I finally fell to

the ground. I was dragging myself along by pulling on the grass

when the last shot passed between my ear and shoulder and buried

itself in the ground in front of me. The guards were then less

than seventy five yards away, and I just had time to turn over,

raise myself to a half-sitting and half-lying posture and elevate

my hands above my head as a sign that I surrendered, before they

were on me.

With fiendish fury the first guard, turning his gun end for end

and grasping it by the muzzle, rushed on me, and dealt me a smashing

blow on the head. It knocked me unconscious and I rolled down

the hill. When I came to my senses I was lying in a

shallow ditch at the foot of the hill and the guards were cursing